The Evolution of the Art of Peace

Yoga is that fitness stuff where people twist themselves into pretzels, right? Tai Chi is that slow motion exercise that old people do in the park. Kung Fu is that fancy martial art where you get to spin and fly through the air. And Jiu-Jitsu is what MMA fighters use in those cage matches to beat each other into hamburger. What do any of those have to do with feeling safe when you walk to your car at night?

Interestingly, these four very different systems all share a common and intertwined origin in ancient India. It was in that far-away soil so very long ago that these seed ideas sprouted, and from there many branches have grown through nearly every culture on earth. While a complete understanding of the histories is not necessary, most of us find it helpful to at least understand where it all came from. In very broad brushstrokes, we will paint a picture of the Art of Peace.

Yoga

YOGA is the science of focus and control of the mind. Originally the emphasis was on mindfulness within your chosen path, with meditation being the most important practice. Asana meant only the way to sit in prolonged meditation, as the modern stretches and poses would not be added until centuries later.

What we know about the origins of yoga comes from a wide variety of sources: ancient texts, oral traditions, dance and religious ritual. The first written history of yoga comes from the ancient Hindu spiritual texts knows as the Vedas. In the beginning, yoga was a purely consciousness-oriented practice, devoted to uniting the individual mind with the cosmic or universal consciousness. Since Spandex had not yet been invented, practice centered around meditation and mantra, repetitive singing or chanting.

Towards the end of the Vedic period – around the first millennium BCE – another set of ancient texts called the Upanishads were written. The yoga described within these books is very different from what is practiced in modern yoga studios around the world, but we can definitely see the connections in both language and philosophy. It is here that we are introduced to concepts such as prana, or the vital energy of living beings.

One of the most popular of the Upanishads is a book called the Bhagavad Gita which details a conversation between the warrior-prince Arjuna and his charioteer, Krisha, on the eve of an epic battle. Distraught and confused about the morality of war, Arjuna is counseled by Lord Krisna as to his duties as a warrior and a prince. This text details different forms of yoga rooted in service to others, pursuit of knowledge and religious devotion. The concept of dharma, or sacred duty, is introduced, along with other guiding principles for gaining spiritual liberation.

What many consider to be the most important ancient book on yoga – The Yoga Sutras – was written by the sage Patanjali thousands of years ago. In just 196 short statements, Patanjali introduces the concepts of asana, ethical behavior, pranayama or breath control, and dharana or focused concentration. Asana is still considered only a posture or stable seat for meditation at this point. So far we haven't done a single stretch, back-bend or head-stand. To get physical, we'll need to jump to a different track.

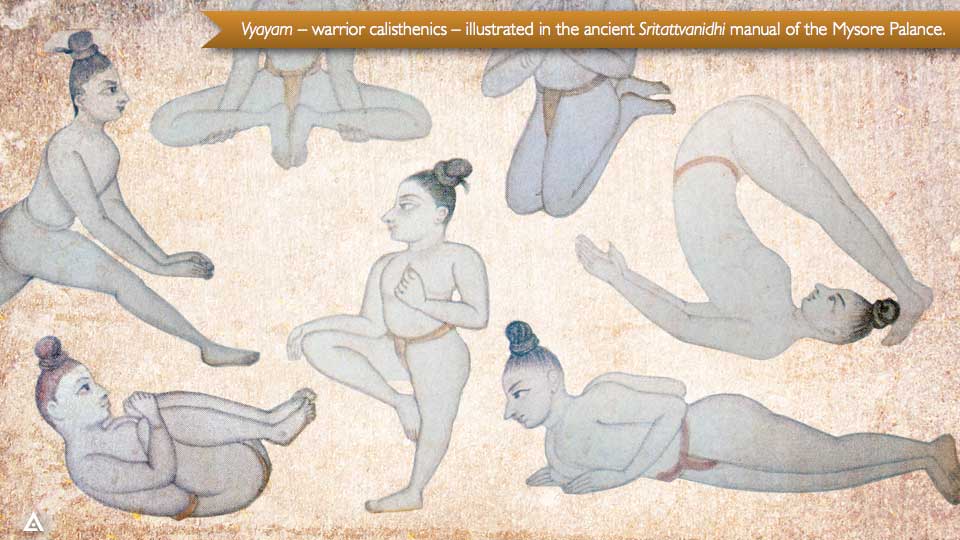

The Vyayam of the Kshatriya

VYAYAM is the science of fitness and development of the body. Developed as warrior calisthenics, the goal of vyayam was to build functional strength, mobility, flexibility, structural integration and endurance. Many of the poses in modern yoga are drawn directly from these exercises.

Ancient India was divided into castes or layers in a social hierarchy. The four most well-known castes were the Brahmins, Vaishyas, Shudras and Kshatriyas. At this point in time, yoga was the domain of the Brahmins, those devoted to attaining the highest spiritual knowledge. The Vaishyas were the farmers and tradesmen, and the Shudras were the servant class. The Kshatriya were the warriors and the ruling class.

As warriors, one of the most important fields of study was the martial arts. Collectively known as Mallavidya (literally, "Fight Science"), the Kshatriya trained in weapons fighting, striking, kicking and even pressure-point attacks. The most important of the martial arts, however, was grappling. Many different styles of grappling and wresting were developed, often named after legendary warriors or Hindu gods.

For example, Hanumanti Mallavidya took its name from the Hindu deity Hanuman – the Monkey God – and concentrated on technical superiority of grappling skill. Jambuvanti used locks and holds to force the opponent into submission, Jarasandhi focused on breaking the limbs and joints, and Bhimaseni emphasized bodybuilding and overcoming an opponent with size, strength and speed.

Vitally important to all of the Kshatriya warriors was their physical fitness. They had to be strong, flexible, fast and have superior endurance. This was achieved through a disciplined lifestyle, strict attention to nutrition, and the practice of vyayam, or "warrior calisthenics."

Chief among these exercises were a unique variation of push-ups called danda, powerful squats known as baithak, a head-stand named shirshasana, bridges and back-bends, and a flowing sequence of calisthenic motions called surya namaskara, or "sun salutations."

Bodhidharma

BODHIDHARMA was a Kshatriya warrior-prince who became a Buddhist priest, and is credited with fusing practices from yoga with training in the martial arts. According to legend, he traveled throughout Asia where his teaching spread from the Shaolin temples of China to the samurai clans of Japan.

By the 5th century CE, the yoga practices of the Brahmins and the vyayam practices of the Kshatriya began to merge as many warriors began to embrace a more spiritual path. Of particular interest is a prince from the Tamil Pallava kingdom of Kanchipuram. Known as Bodhidharma, he blended a lifetime of training in the warrior arts of Mallavidya with the Yogic practices of breath control and concentrated focus.

As Bodhidharma became a Buddhist priest, he embraced the concepts of Ahimsa in it's most complete form, that not only should you not use violence to get what you desire, but also that it is a moral imperative that you should not allow violence to be used against yourself or other innocents. His martial training evolved into Rakshana Mallavidya, or knowledge of defensive combat. His insights led him to renounce his throne, become the 28th Patriarch of Buddhism, and ultimately leave India to spread his knowledge around the world.

Travelling first to China, Bodhidharma spent many years at the Buddhist temples of Shaolin where he taught his new concepts to the monks. The emphasis on mental and physical conditioning led to the Shaolin monks becoming world-renown for their skill in the martial arts. Branching from Bodhidharma's teaching are the various forms of Shaolin Kung Fu, qigong (energy work) and taijiquan.

According to legend, Bodhidharma then travelled to various temples in Southeast Asia spreading Chan Buddhism and his new concepts on the martial arts. In Japan he is known as Daruma and is considered the founder of Zen Buddhism and a major influence on the martial arts of the samurai.

Much like the Indian Kshatriya, the samurai were a warrior class whose primary field of study was the martial arts. Along with swordsmanship and archery, the samurai became known for their skill in unarmed combat, specifically with a brutal style of close-range combat known as jiu-jitsu.

The Chinese Connection

THE SHAOLIN TEMPLES became centers for martial arts innovation for hundreds of years. Of the many well-known martial arts styles that originated here, Taijiquan and Wing Chun are two of the most famous.

The legendary Zhang Sanfeng lived in the period of Chinese history known as the Song Dynasty (960-1279). As a Shaolin monk, he had mastered all of the Kung Fu styles of Shaolin, but grew increasingly dissatisfied with the Buddhist emphasis on separating body from mind. Seeking another path, he converted to Taoism and retired to a monastery in the Wudang Mountains. There, he blended a Taoist version of yoga called Daoyin with Snake and Crane styles of Shaolin Kung Fu to produce a new martial arts style called Taijiquan – sometimes written as Tai Chi Ch'uan.

The word Taiji represents the dynamic moment when the opposing forces of Yin and Yang are either split apart or fused together. The Taiji symbol itself demonstrates this careful balance, and is commonly known as the Yin/Yang circle. Drawing from this understanding of innate balance, Taiji developed techniques based on "uprooting," throwing and knocking an opponent to the ground.

Hundreds of years later, during the chaotic transition from the Ming to the Qing Dynasties of the mid-1600's, the Snake and Crane forms of Shaolin Kung Fu were re-invented in yet another form. A Buddhist nun and one of the Five Elders of the Southern Shaolin Temple, the legendary Ng Mui, synthesized a form of Shaolin Kung Fu that incorporated the principles of Wudang Taijiquan, could be learned in a very short period of time, and could be utilized by women to defend against bigger and stronger men. She taught the new style to a local village girl named Yim Wing Chun, who then used it to defeat a ruthless local warlord. The new style has borne Wing Chun's name ever since.

The Reinvention of Yoga and the Martial Arts

In the late 1800's and early 1900's pioneers such as T. Krishnamacharya in India, Yang Chengfu in China and Jigoro Kano in Japan re-imagined yoga and the martial arts. Yoga was transformed from a meditation-based practice to one that integrated the fitness of the entire body. Taiji grew into a popular method of health and revitalization. Jiu-Jitsu evolved from a lethal battlefield art into a sustainable practice for physical fitness, self-defense and sport.

Over hundreds of years, the arts of yoga, taijiquan and jiu-jitsu continued to branch and evolve. In 15th century India, elements of yoga and vyayam were combined in the practice of Hatha Yoga, introducing a small number of asana for developing the strength and flexibility of the body along with the more traditional practices for controlling breath and developing concentration. In China and Japan, the original teaching had branched into hundreds of different forms of Kung Fu and Jiu-Jitsu. But these powerful practices also became known as a threat.

With the British conquest of India, the practices of yoga and mallavidya were disdained and discouraged, and so largely driven underground. At roughly the same time, the American Commodore Matthew Perry arrived in Japan and became the catalyst for the Meiji Restoration which forever changed Japanese society – and outlawed the samurai. The Chinese fared no better, as during the transition from the Qing to Ming dynasties the Shaolin temples were burned and the monks imprisoned, killed or forced to flee.

It wasn't until the dawn of the 20th century that many of these arts began to re-emerge. A renewed interest in physical culture began to spread throughout India with influence from British, Scandinavian and American physical education programs. This set the stage for an evolution in Hatha Yoga by Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, who drew much of his new postural forms directly from the Kshatriya Vyayam traditions of the Mysore Palace. Many of Krishnamacharya's students continued to evolve the ideas of physical yoga and even spread them to the west, including K. Pattabhi Jois, B. K. S. Iyengar, Indra Devi and Krishnamacharya's son T. K. V. Desikachar.

In China, Yang Chengfu vowed to change the overall poor health and fitness of the Chinese people by re-inventing his family style of Yang Taiji into a format that emphasized health and vitality. He discarded or modified many of the combat techniques in favor of smooth, flowing and graceful movements that could be practiced by people of all levels of athletic ability. His students continued to adapt and expand his work, with modern pioneers such as Cheng Man-ch'ing, T. T. Liang and William C. C. Chen helping to bring the practice to the Western world.

In Japan, Jigoro Kano began a systematic study and re-invention of Jiu-Jitsu. He called his new art Judo, the Gentle Way. One of the most important innovations in Kano's Judo was the emphasis placed on randori, or free sparring practice with a fully resisting opponent. Kano also concentrated on techniques that could be both practical for self-defense and trained in a safe manner. As Judo continued to grow in popularity, it, too, began to spread to the West.

The Revolution of Modern Jiu-Jitsu and Wing Chun

“Jiu-Jitsu is for the protection of the individual, the older man, the weak, the child, the lady and the young woman – anyone who doesn't have the physical attributes to defend themselves.” This quote from Helio Gracie, the founder of Gracie Jiu-Jitsu, perfectly sums up his intention. Small and frail himself, Helio proved the effectiveness of his system by fighting opponents who sometimes outweighed him by a hundred pounds.

One of the fighters tasked with taking Kano's Judo to the world was Mitsuyo Maeda. Originally trained in traditional Fusen Ryu Jiu-Jitsu – a style that emphasized grappling skill instead of throwing – Maeda travelled the world before coming to Brazil in 1917. There he met an influential business man named Gastao Gracie who had sons that were interested in the martial arts. Maeda taught the Gracie boys a blend of Kano's Judo and Fusen Ryu Jiu-Jitsu, and they went on to open the Gracie Jiu-Jitsu Academy in 1925.

The youngest of the Gracie brothers was Helio Gracie, who was 16 when the Academy opened. Small and weak, Helio lacked the explosive strength and athleticism required to master the Japanese Jiu-Jitsu that his older brothers taught. But instead of giving up, he deconstructed the Japanese art and reassembled something unique. He created a system that allowed a smaller, weaker person like himself to avoid injury and even defeat a bigger, stronger attacker.

Helio Gracie developed his system purely as a means of self-defense. It was tested and refined first between students and brothers, later in matches between schools. Helio himself finally took to the ring in no-holds-barred matches to both test his system and prove its effectiveness.

“Once I believed the techniques worked well for someone weak and small like me, I was convinced that they would work for everybody,” Helio explained. “This was the reason I went into the ring. I wanted my students to know that I was willing to put my neck on the line to prove that what I was teaching them really worked. Fighting was the only way to test my beliefs.”

It was those competitive fights that first got everyone’s attention, and what caused Gracie Jiu-Jitsu to grow in popularity. In 1993, Helio’s son Rorion introduced Gracie Jiu-Jitsu to the world through the first Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC). Royce Gracie, the smallest of the fighters, emerged from the “no rules, no time limits” event as the world champion. This shocking upset was the birth of modern MMA.

At the same time that Helio Gracie was re-inventing Jiu-Jitsu, a similarly-sized man was deconstructing Wing Chun in Hong Kong. Ip Man had been trained in the traditional forms of Wing Chun Kung Fu, but also knew that the art had to evolve. Using himself and his students as his testing ground, Ip Man began to streamline Wing Chun to make it more compact and efficient.

Instead of trying to teach thousands of possible techniques, Ip Man focused on the underlying concepts and principles of Wing Chun. He saw that once students understood the seed ideas, techniques could be adapted and expressed easily. But breaking from tradition was not popular at the time, and Ip Man's students were forced to prove the art's effectiveness.

In the 1950's – long before the invention of televised cage matches – Ip Man's students put Wing Chun to the test through challenge fights called beimo. These bare-knuckle "Kung Fu elimination contests" had no rules, protective equipment or time limits. Fights were staged on streets, flat rooftops and back alleys. Through dozens of these these competitions, Ip Man's Wing Chun gained the reputation of being brutally effective and soared in popularity.

Ip Man's students became sifus or teachers in their own right, opened new Wing Chun schools, and spread the art beyond the borders of Hong Kong. By the 1970's, students such as Wong Shun Leung, William Cheung, Ho Kam Ming, Moy Yat, and martial arts super-star Bruce Lee had begun to spread Wing Chun to the rest of the world.

The Branches Intertwine

“Jiu-Jitsu, Gracie tells me, is the oldest martial art in the world. The Gracies claim the system was devised by Hindu ascetics in about 2000 B.C.E. (about the same time yoga originated) because their practice of ahimsa, or nonviolence, forbade them from carrying weapons or injuring anyone. With their deep knowledge of physiology, the ancient masters devised a system of joint locks, chokes, and similar techniques that enabled them to protect themselves, but with minimal injury to their opponents.”

– Excerpt from The Peaceful Warrior by Michael Corbett for Yoga Journal

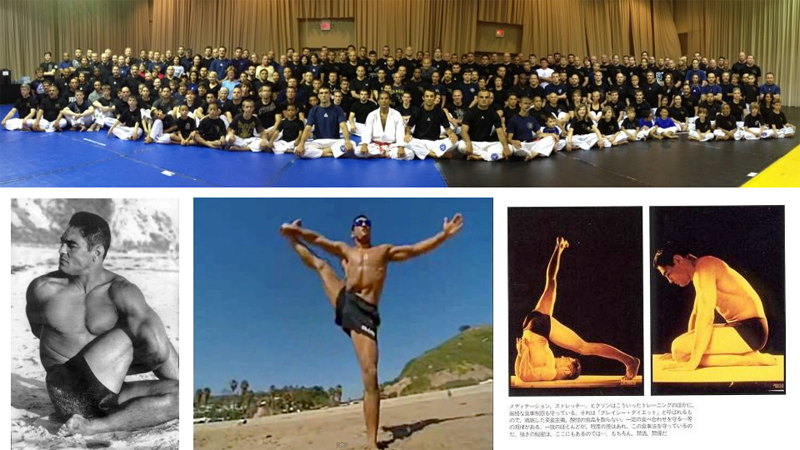

The worlds of yoga and Gracie Jiu-Jitsu met again in Rio de Janeiro in 1980 when Rickson Gracie, son of Helio Gracie, began training with Orlando Cane, a two-time world champion in the Army pentathalon and a professional yoga teacher. Cane introduced Gracie to yoga's postures, integration, concentration and pranayama breathing techniques.

“Once I began practicing it, I noticed the effects immediately,” Gracie told Yoga Journal. “My senses became sharper, increasing my awareness of my body and surroundings. My speed, my coordination, my balance, my emotional control – everything improved greatly.”

Over the next dozen years, Rickson Gracie integrated yoga and pranayama first into his workouts and later into actual competitive fighting, where increased focus and emotional control gave him a formidable advantage. The practice of merging yoga with jiu-jitsu continued to spread to his students, brothers and the extended jiu-jitsu world. Today, it is common to see yoga used as warm-ups and cool-downs in jiu-jitsu schools all over the Earth. Coming full circle, warriors are once again embracing yoga.

In the years following the first UFC, the grappling techniques of Gracie Jiu-Jitsu were often paired with the striking capabilities of other arts such as Western boxing or Muay Thai. When Gracie Jiu-Jitsu met Wing Chun, the similarities in concept and philosophy were seen to be a perfect fit. A new course was plotted when grandmasters of each system met for the "Double Impact" event of 2007. At this seminar, Carlson Gracie and Samuel Kwok encouraged their respective students to cross-train in both arts. Blending or "mixing" martial arts became an accepted practice around the world.

The Synthesis of Fearless•Yoga

Today, yoga has evolved into dozens of branches that emphasize different characteristics of practice. Ashtanga, Bikram, Hatha, Iyengar and Vinyasa Yoga – and many others not listed here – have a dedicated following around the world. Traditional vyayam calisthenics have evolved into CrossFit, TacFit, Ginastica Natural and similar programs that emphasize functional strength. Taijiquan has become a mainstream therapeutic exercise found in many gyms, health clubs and health-care facilities. Wing Chun has experienced renewed popularity thanks to the Ip Man series of Hong Kong movies. And jiu-jitsu has moved from the battlefields of medieval Japan to become the dominate combat sport in the world-wide phenomenon of Mixed Martial Arts.

These arts have evolved into very different individual disciplines. However, now you have seen how they share a common, intertwined origin, and understand how they synergistically fit together. To utilize the material in Fearless•Yoga, you don't have to meditate in lotus posture, chant in Sanskrit, pound the heavy bags or flip tractor tires until you puke. You should simply be able to recognize the seed idea when you see it: the mindfulness and focus of yoga, the effortless flow from taiji, and the use of concept-based defensive tactics from Wing Chun and jiu-jitsu.

Next: Ignition

There is an interesting theme that runs through the evolution of these particular arts: the revolutionaries were just ordinary people. Modern yoga was streamlined so that normal people with households and jobs could do it. Yang Chengfu taught taiji for the health and vitality of everyone, no matter how young, old, frail or sickly. Jigaro Kano's dream was to see jiu-jitsu taught as physical education in high school. Ip Man and Helio Gracie proved that you did not have to be big, strong and athletic just to defend yourself.

These arts are not the exclusive domain of elite athletes, the thin and flexible, or the strong and powerful. These arts work for everyone. Including YOU. The next step is to strike that spark that transforms this from a good idea to a solid practice. We call this next phase IGNITION.